My memory is astonishingly volatile and during the last years I’ve been under a heavy context switch, so I keep some dirty gists with recipes for different topics, from PostgreSQL to Linux. They need some refactoring, so maybe I can kill two birds with one stone and publish them here after the cleanup, they might be useful for somebody else.

Disclaimer: no, I don’t use (almost) any alias or small script. To save some keystrokes bash history is good

enough, and learning the actual command will always be valuable. Currently, my only exception is gittree.

Workflow

Basic stuff, you probably want to skip this section, this is more a brain dump.

$ git status # First normal step, as a double-check for files not added to the repo or unwanted changes

$ git checkout -b my_new_branch # Let's begin

$ git add file_1 file_2

$ git commit -a -m "Message" # If no long explanation is required, or ...

$ git commit -a # ... if a long comment is convenient (see later)

$ git fetch master

$ git rebase master # If it's safe or ...

$ git merge master # ... if it's not and

$ git push # If there's no history rewrite or ...

$ git push --force-with-lease # ... if it's not (see later)

A must-have: just like in bash you can go to the “previous path” with cd -, in git you can go to the previous branch

with git checkout -.

Commit messages: long or short?

Like many other things, this is often a matter of taste and there’s no best answer. Just adopting your team choice is good enough.

If I have to choose, I’d say short (single sentence, with -m), because better code or, more flexibly, a comment inside

the code, is likely a better choice (seeing a comment and reading it is more convenient than traversing git history most

of the times).

rebase vs merge, forcing

If you created a branch, rebasing the original one to keep yours up-to-date until the first push should be mandatory because it has little cost and a lot of return. The problems begin when you’ve already pushed.

If the branch has already been pushed and other people are also working on it, I always use merge. It pollutes the

history, but alternatives can lead to messy repositories and even losing code.

That advice AFAIK is the normal practice. The fuzzy area is what to do when you’ve already pushed code.

Pushing often is convenient both for safety reasons (to avoid losing work) and for communication (“ey, take a look at

this WIP and tell me if…). Some people say that you should never, ever, rewrite history. I disagree. IMHO, even if

you’ve pushed code, as long as anybody else has touched it, it’s right. And while you can’t know what are people doing,

you can be sure that only you pushed, with --force-with-lease. It checks based on the expected references, if you want

more details, this is a good explanation.

How to pull after a force? git reset origin/my_branch --hard.

WIP

There’s another common pattern in my workflow, pushing code that is still not finished:

$ git add .

$ git commit -a -m "WIP" # "This is work in progress and shouldn't get to master"

$ git push # Leaving today :wave:

...

$ git commit -a --amend # Continuing WIP, no relevant step that deserves its own commit

...

$ git commit -a --amend # Now change the message with the right one

$ git push --force-with-lease

The problem with that is that you must remember that you’re working on top of a WIP commit because if you don’t and

add commits, then removing it through squashing can become tricky. In the past, I created some git hooks, but

they were an annoyance (maybe I’ll eventually try again, who knows).

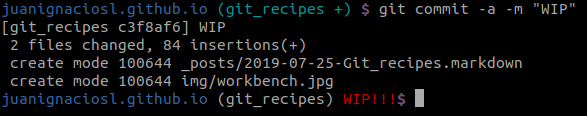

Now have this

in my .bashrc

so the shell prompt display it:

if [[ `git log -n 1 --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit` =~ "WIP" ]]; then # if last commit is a WIP

__wip_warn="${RED}WIP!!!"

Output:

juanignaciosl.github.io (git_recipes +) $ git commit -a -m "WIP"

[git_recipes c3f8af6] WIP

2 files changed, 84 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 _posts/2019-07-25-Git_recipes.markdown

create mode 100644 img/workbench.jpg

juanignaciosl.github.io (git_recipes) WIP!!!$

Stashing

I use stashing a lot, specially when I have to move quickly between branches.

git stash: Stash current changes.git stash pop: unstash and merge stored changes.git stash apply: merge stored changes without unstashing (you can later remove it withgit stash drop).

Anyway, I’m using the previous WIP strategy more and more. It’s easy to forget that you stashed something, and

doing two consecutive git stash pop by mistake can lead to big messes :_)

Cleaning the history

I like doing a lot of commits, each of one encompassing a single step. Sometimes you discover steps that are strongly

related but aren’t consecutive, so a simple --amend is not enough. In those cases, interactive rebase is useful

and simple to use once you get used to. For example, with this command you can reorder and squash the last three

commits:

$ git rebase -i HEAD~3

If you want to rebase to master and at the same time rearrange the commits in your branch (thanks, @matallo:

$ git rebase -i master

If you need to rebase back to the first commit:

git rebase -i --root master

Finding bugs

I always said that if you find a new bug, reasoning based on changes (“what has changed since the last time that I

think that it worked”) was a suboptimal strategy, but git provides a great tool to chase bugs that removes the mental

load: git-bisect. It provides a binary search through git commits, from the one that you know that worked.

Here’s a great tutorial about it.

GitHub

Hub is “an extension to command-line git that helps you do everyday GitHub tasks without ever leaving the terminal.”

Commit automation

Links

If you navigate through a file, the address bar contains the reference inside a branch, which can change, so it’s not

a true permalink. If you want to share a GitHub link, press y before, the URL will change to the commit hash.

Misc stuff

Credentials

Forwarding

Sometimes you want your local keys available in a server (for example, when you create a transient instance in a

cloud provider and you just want to pull a git repo). Using ssh -A, if the remote system allows it, works. Keep in

mind ssh man page warning:

-A Enables forwarding of the authentication agent connection. This can also be specified on a per-host basis in a configuration file.

Agent forwarding should be enabled with caution. Users with the ability to bypass file permissions on the remote host (for the agent's UNIX-domain socket) can access the local agent through

the forwarded connection. An attacker cannot obtain key material from the agent, however they can perform operations on the keys that enable them to authenticate using the identities loaded

into the agent.

macOS

I’m currently using Linux (Ubuntu 19.04) and I think that it worked right out of the box (I didn’t write anything in my guide and there’s nothing at my configuration files).

In macOS things were different:

eval "$(ssh-agent -s)"git config --global credential.helper osxkeychain- GitHub SSH Keys

ssh-add -K ~/.ssh/id_rsa_githubhttp://superuser.com/a/1155833

Instructions for macOS Sierra

ssh-add -K ~/.ssh/id_rsa Note: change the path to where your id_rsa key is located.

ssh-add -A

Create the following ~/.ssh/config file:

Host *

UseKeychain yes

AddKeysToAgent yes

IdentityFile ~/.ssh/id_rsa

Viewing changes

git log -5 --pretty --oneline: single line per change.git log --all --graph --decorate --oneline --simplify-by-decoration: pretty branch current status.git reflog: displays every change.git diff --ignore-space-at-eol: ignore spaces (workaround for Atom formatter).git diff --cached: changes in files that you’ve already added.git diff mybranch master -- file.ext: compare file between branches.

Comparing changes

git diff --name-status master..6953-Vizjson_3_generation: list changed files.-

git diff master..6953-Vizjson_3_generation -

git shortlog master..6953-Vizjson_3_generation git log master..6953-Vizjson_3_generationgit log __branchA__ ^__branchB__: commits in branch A that aren’t in branch B.git log origin/__branchname__..__branchname__: show diff between local commits and remote commits.

Searching

git log -S puppy: looks for “puppy” in the contents of the commit history.git log --grep $string: looks for$stringpattern (regexp) at messages (thanks to @stbnrivas).-

git log --since=$(date --date="15 day ago" +"%Y-%m-%d"): filter by date. git blame -M: blames original commit, not the move commit.git blame -CCC: looks at all commits in history.

Branching

git branch -r: list remote branches known by local git.git remote update origin --prune: update remote branches list.

Viewing the branching tree (this is my only current alias):

alias gittree='git log --graph --pretty=oneline --abbrev-commit'

Adding changes

git add -p: add step by step (hunks).git rebase -i HEAD~4: interactive rebase.

Cherry-picking:

git cherry-pick [commit]: picks one commit.

Reverting changes

git revert <commit>: applies the inverse of a commit.- Single file:

git checkout 1b4df5b13e5c76aa50b9ba1fd0167a947250c298~1 -- file.rb. git reset: revertsgit add.git reset <commit>:--mixed(default): move the current branch HEAD and index backward to. --soft: moves HEAD, index unchanged.--hard: moves head, changes index and removes changes.

Reverting ammend

# Move the current head so that it's pointing at the old commit

# Leave the index intact for redoing the commit.

# HEAD@{1} gives you "the commit that HEAD pointed at before

# it was moved to where it currently points at". Note that this is

# different from HEAD~1, which gives you "the commit that is the

# parent node of the commit that HEAD is currently pointing to."

git reset --soft HEAD@{1}

# commit the current tree using the commit details of the previous

# HEAD commit. (Note that HEAD@{1} is pointing somewhere different from the

# previous command. It's now pointing at the erroneously amended commit.)

git commit -C HEAD@{1}

Fixing things

git commit --amend: change last comment, but with-ayou can merge current changes with the last commit.- Change commit author.

- Recover deleted file:

git checkout $(git rev-list -n 1 HEAD -- "$file")^ -- "$file"

Teamwork

git shortlog -sn: contributors.- Checking out pull requests locally (pull request from a fork or branch of your repository).

Productivity

- You can add a

[alias]section at.gitconfig. git diff --shortstat "@{0 day ago}": how many lines you’ve written (today).

Cleanup

git remote prune origin [--dry-run]: remove local branches deleted at remote.git clean -n -df: displays local uncommited directory and file modifications. Remove-nto actually delete them.

Patching

- Create patch:

git diff > file.patch - Apply patch:

git apply file.patch

--patch also works with add, checkout and log (@pvrrgrammer):

- With

logit’s like-p, for seeing the diff of the change. - With

add, it interactively asks for action on each change hunk. - With

checkout, it interactively asks for discard action on each change hunk.

Ignoring local files

The .git/info/exclude file has the same format as any .gitignore file. You can also set core.excludesfile to the name of a file containing global patterns.

If you already have unstaged changes you must then run:

git update-index --assume-unchanged [<file>...]

Copying/moving…

- Clone branch to another location:

git archive master | tar x -C /path/to/target/dir.

Submodules

git submodule init && git submodule update: retrieve and update all submodules (alt).